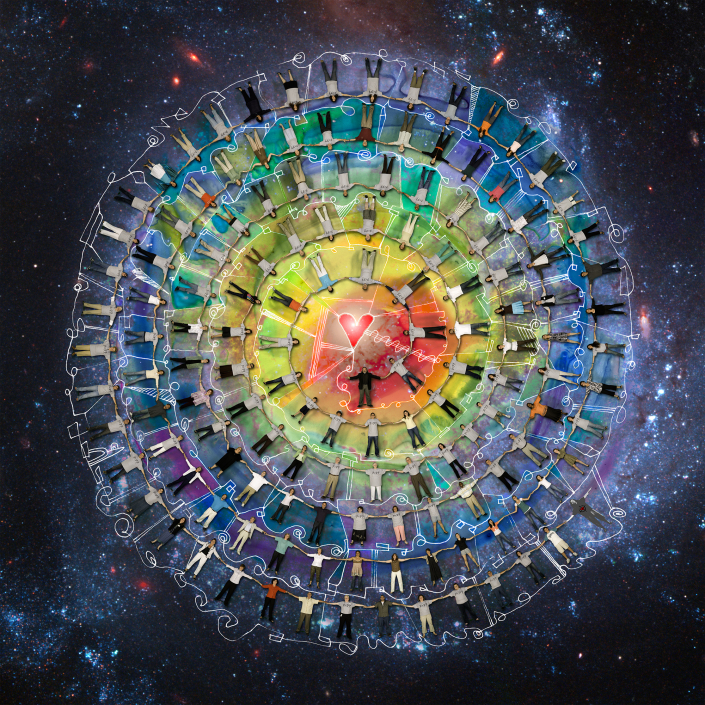

Peace Spiral

A Forum on Forgiveness

The Peace Spiral was created at a special Forum on Forgiveness organized by Father Vazken. – “We need to change our metaphors. If we are to imagine a world with peace, we must speak a language that includes forgiveness, as much as it does tolerance and understanding.”

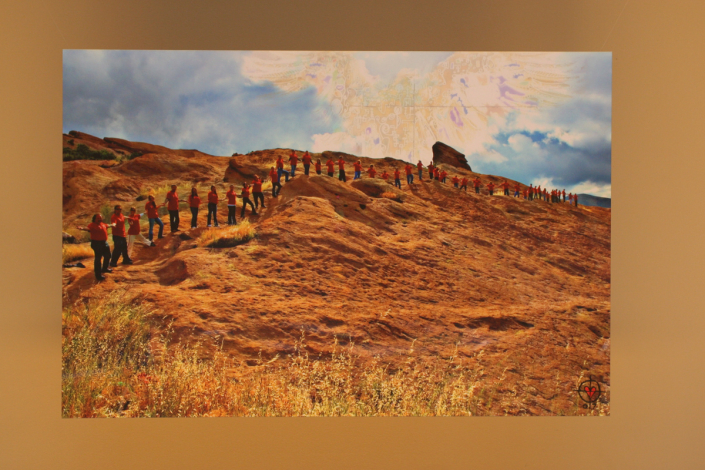

The Peace Spiral was created by setting up a photo studio at the event location and photographing every participant with arms extended, palms open. Then the artwork was created by placing every person into the art, palm touching palm in a cosmic spiral configuration to portray in a visual art form the mission of the event.

A 10 foot by 10 foot tapestry print was created of this work.

a special Forum on Forgiveness has been slated at the All Saints Church in Pasadena. Speakers, discussions, films will all be part of the agenda, as we look at “Local Reconciliation~ Global Peace.”

“It seems that the only language people speak these days is that of war,” said Fr. Vazken in his weekly message. “We need to change our metaphors. If we are to imagine a world with peace, we must speak a language that includes forgiveness, as much as it does tolerance and understanding.” Get the Details

Paul Freedman’s new documentary on Darfur will be screened at the Forum. The film, narrated by George Clooney is powerful in content and message. A question and answer session with the producer will follow.

07/07/07 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF FORGIVENESS

July 6 & 7, 2007

Friday 6–10PM; Saturday 9AM-3PM

In His Shoes Ministries, in collaboration and cooperation with All Saints Church is hosting this event for our times: ”Local Reconciliation; Global Peace: A Forum on Forgiveness”

Join us for a two day forum on forgiveness: Discussions • Lectures • Break Out Groups Explore hope for Peace in our World.

Participants:

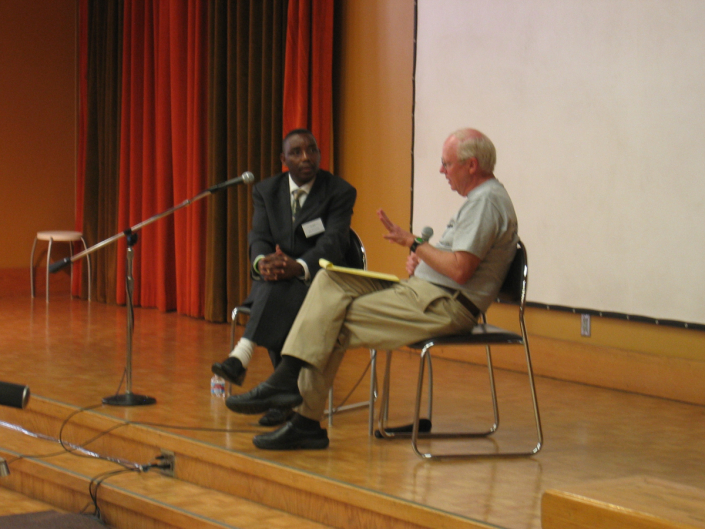

- Benjamin Kayumba – survivor ofthe Rwandan Genocide (1994) confronts the rapist & murderer of his parents.

- Leticia Aguirre – mother of Raul Aguirre, who was slain in street gang warfare, forgives her son’s murderer during the courtroom trial. A story like no other…

- Fr. Vazken Movsesian – lays out a plan for forgiveness that transcends the personal and affects the global realm, with examples from a pure orthodox vantage point.

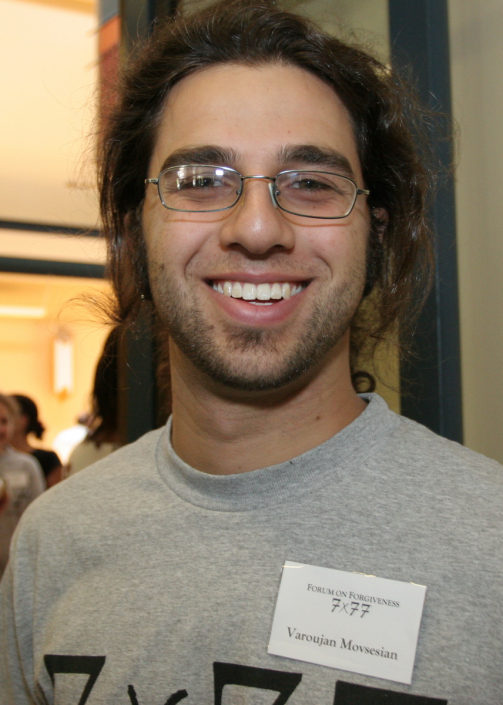

- Gregory Beylerian – artist and creator of the acclaimed 7×77 art piece (2005), will be developing his latest creation with conference participants.

- Linda Maxwell – Co-Executive Director of We Care For Youth, brings together the community for a Mandala for Peace.

Ben Kayumba Named In His Shoes Person of the Year

Read Ben Kaumba’s story below in the Los Angeles Times.

Preaching the power of forgiveness many times over

By Teresa Watanabe

Times Staff Writer

July 7, 2007

One is an Armenian American priest who resides in Pasadena, the other a Rwandan minister who lives half a world away in Kigali. Across culture and distance, however, Father Vazken Movsesian and Benjamin Kayumba share a powerful if tragic bond: their peoples’ traumatic legacy of genocide.

Movsesian lost dozens of relatives, including a grandfather, during the early 20th century massacre of about 1.2 million Armenians under the Ottoman Empire, which became the modern republic of Turkey.

For Kayumba, the scars are more recent. He lost 152 relatives, including both parents, during the 1994 slaughter of more than 800,000 minority Tutsis and moderate Hutus by Hutu extremist militias.

The men also share a conviction: that only forgiveness can ultimately heal themselves and their communities.

It’s a difficult journey. During an interview this week, Kayumba recalled that his mother was stripped naked, beaten, stabbed through the chest and left to die on a road until dogs came to eat her flesh. In time, Kayumba learned to forgive her murderer, and the anger that weighed Kayumba down vanished.

“From that night, I was free,” he said.

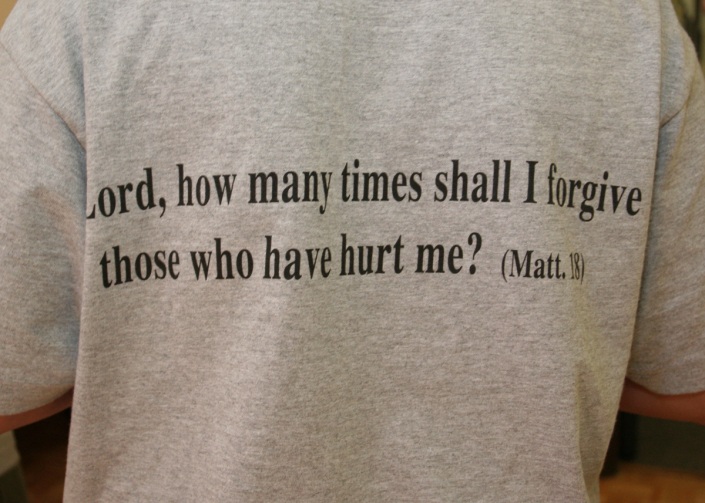

Kayumba and Movsesian will share that lesson today at a “forgiveness forum” carefully scheduled for July 7, 2007; it’s a symbolic way of following Jesus’ exhortation to forgive “not seven times but seven times 77,” according to the ancient Armenian Orthodox translation of the Bible.

The forum at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, organized by Movsesian’s In His Shoes Ministries, will also feature other speakers and artists on the forgiveness theme, including a Latina mother who met and forgave an Armenian gang member who killed her son.

Movsesian said his message has drawn opposition from some Armenian Americans. But he said he intends to keep preaching unconditional Christian forgiveness, following Jesus’ actions on the cross.

“I’ve forgiven the Turks,” he said. “Now I can move on with my life.”

The two men crossed paths for the first time last year. Movsesian journeyed to Rwanda at the invitation of Donald Miller, a USC professor of religion and sociology who has co-written a book on the Armenian genocide and is compiling an oral history of Rwandan survivors.

Movsesian said the trip immediately produced powerful emotional moments. After arriving in Kigali, the group went to visit a mass grave for 260,000 victims. At the Genocide Museum, Movsesian said, he heard story after story of survivors — how Tutsi women escaped Hutu soldiers by jumping into the Nile River, for instance.

Suddenly, Movsesian said, it hit him. His grandmother had told of Armenian women eight decades earlier jumping into the Euphrates River to escape the Turks. He said he began “crying like a baby.”

“We haven’t changed,” Movsesian said in an interview this week, shaking his head. “Nothing has changed.”

Shortly after his visit to the Genocide Museum, he met Kayumba, a field activities coordinator for the Kigali-based Solace Ministries, a faith-based nonprofit organization offering counseling, child care, medical aid and other services for widows and orphans. Sharing their faith and family stories, the two men also discovered common convictions about forgiveness.

For Movsesian, the ideas about forgiveness first came in 2005 as he planned his ministry’s commemoration of the 90th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, observed each year on April 24.

The Armenian American community has protested to the Turkish government, which denies a genocide took place, pushed for a presidential resolution on the issue and held annual memorials.

“We’ve done everything but what we’re supposed to do as Christians — we haven’t forgiven,” Movsesian said.

That year, he began preaching that message — taking care to emphasize that forgiving does not mean forgetting — and took young members of his ministry to the desert to form a human chain symbolizing forgiveness.

For Kayumba, the transformative moment came unexpectedly. Two months after the genocide had ended, he drove from Kigali to his family’s village to face his mother’s killer. Kayumba learned his identity through other villagers. The two men had grown up together. When he saw the man walking along a road, Kayumba said, his anger surged and he tried to run the man over.

The young man dived into a ditch, unharmed. As Kayumba jumped out of the car and made for the trembling man, he said, a voice filled his head.

“Don’t take revenge,” said the voice he identifies as the Holy Spirit. “Revenge is mine.”

Kayumba said he looked into the eyes of his mother’s killer. The man did not ask for forgiveness, but Kayumba did — for trying to kill the man. Kayumba offered absolution as well. His mother’s murderer could go. Kayumba had forgiven him.

“The anger, frustration and trauma was totally gone,” Kayumba said. “Instead, I immediately felt relief, peace and love for this person. That’s why I say forgiveness is for us, our own benefit. Hatred and anger can kill you.”

Whether the urge to kill is hard-wired into the human heart or not, as one genocide seems to give way to another, the two men prefer to believe in hope.

“We want to end this,” Movsesian said. “We don’t want to have to come back and talk about genocide again.”

But work remains to be done, Kayumba and Movsesian say. The priest’s In His Shoes Ministries, along with All Saints Episcopal Church’s New Vision Partners ministry, is coordinating donations for Kayumba’s Solace Ministries.

They are also sharing ideas about how to take action against another genocide — in the Darfur region of Sudan.

They teach a message of forgiving

Forum shares stories of two who lost loved ones at the hands of others and their capacity to forgive.

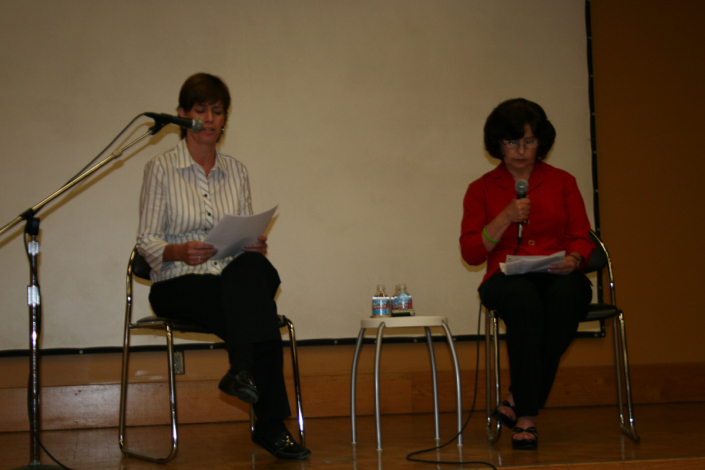

Caption – picture on right: Leticia Aguirre spoke about her experiences with forgiving one of her son’s murderers during the Forum of Forgiveness at All Saint’s Church in Pasadena Saturday morning. — Alex Collins / News-Press

Leticia Aguirre and Ben Kayumba, strangers to each other whose native countries of Mexico and Rwanda are separated by an ocean and a world of cultural differences, share a tragic bond — both know how it feels to lose a family member to murder.

Aguirre, a longtime Glendale resident, lost her son Raul Aguirre on May 5, 2000, when he tried to break-up a gang-related scuffle outside Hoover High School. Raul, who was not in a gang, got caught in the mix and a knife meant for another boy ended up in the 17-year-old’s heart.

Kayumba’s mother, father and more than 150 of his extended family members — and the vast majority of those living in their village — were slain by Hutu rebels during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, he said.

Their stories were the focus of Forum on Forgiveness, a two-day event hosted by Glendale-based nonprofit organization In His Shoes Ministries, at All Saints Church in Pasadena on Saturday.

Aguirre has told her story numerous times in the past seven years, but its lesson is timeless, said Fr. Vazken Movsesian, In His Shoes Ministries executive director.

“It is the most profound and moving story I’ve ever heard,” Movsesian said.

For Aguirre, the story begins with dinner preparation on a usual Friday afternoon in 2000.

Raul was late coming home from school, she said. Just as Leticia Aguirre started to worry, the phone rang and brought news that her son was hurt in a fight.

Three hours later, after a team of doctors failed to save the boy on the operating table, Raul died, she said.

“That moment was the most horrible in my life,” Aguirre said, through a translator. “I felt that I would die, but the worst is that I didn’t die, that I had to live on second by second.”

And second by second for three years, Aguirre endured the trials of her son’s killers.

“Every day of that trial I was there and I wanted justice to be done,” Aguirre said. “In court I saw the mothers of the gang members kissing crosses and praying to God to forgive their sons and I thought how difficult this must be for God.”

But when Rafael Gevorgyan, one of three gang members tried for being involved in Raul’s death, begged Aguirre’s forgiveness on the final day of his trial, she gave it to him, she said.

“I saw a boy, almost a child, in a situation so grave asking for forgiveness,” she said. “I felt huge compassion and huge tenderness.”

To this day, Aguirre sends and receives letters from Gevorgyan, who is serving a maximum 18-year prison sentence for manslaughter. Aguirre is hoping that a pending appeal that would shorten Gevorgyan’s sentence is granted, she said.

Kayumba, who works for a nongovernmental organization in Rwanda, shared on Saturday a similarly tragic account of the death of his mother — who was stripped naked, stabbed in the chest, and left in the village center to be scavenged by dogs, he said.

When Kayumba, who had escaped his village before the raids in 1994, returned to his home, few traces of his community remained, he said.

The only relics were stories of his family members’ deaths told by a few survivors, one of which pointed Kayumba to his mother’s killer. In a fit of rage, Kayumba found the man, engaged him in a violent scuffle, but held off when he realized that he was moments from perpetrating the same act he sought to revenge.

“What I was going to do is what he did, so I asked him for forgiveness,” said Kayumba, recalling his message to his mother’s killer. “He was just shaking.”

Kayumba and Aguirre’s story left many in the All Saints Church audience shaking and teary as well.

“It’s actually traumatizing listening to these stories,” said Donald Miller, executive director of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at USC, who moderated Kayumba’s testimony. “There’s a sense that if you let these stories seep into your soul, you’re never quite the same.”

- RYAN VAILLANCOURT covers business and politics. He may be reached at (818) 637-3215 or by e-mail at ryan.vaillancourtlatimes.com.

Could you forgive your son’s murderer?

by Brandon Lowrey to The Armenian Reporter

PASADENA, Calif.7 – Leticia Aguirre never got to throw her son his 18th birthday party.

On May 5, 2000, Raul Aguirre, 17, didn’t come home from school. Leticia Aguirre grew worried as she began making dinner. The school called, saying he had been hurt. Raul was stabbed once in the back and twice in the heart by teenage Armenian gang members as he tried to break up a fight involving one of his friends. He died just a few hours after his family rushed to the hospital.

Raul was not involved with gangs.

During his sentencing, one of the young killers begged Leticia’s forgiveness. And for just a moment, she put herself in his shoes – he was scared, and practically a child. The 19-year-old, who was 15 at the time of the murder, was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Justice was served, and it was time to forgive him, she told listeners Saturday at the Forum on Forgiveness.

The forum operated on a simple principle: In order to break the cycle of violence, one must learn compassion, sympathy, and forgiveness.

Father Vazken Movsesian, a priest at Saint Peter Armenian Church and Youth Ministries Center, founded the group as a way of dealing with the Armenian Genocide.

Armenians, Movsesian said, have been caught up in seeking recognition for their genocide.

“In a sense, we don’t need the recognition. We already know it happened,” he said. Meanwhile, the atrocities in Darfur are ongoing. “It’s the only genocide we can actually do something about.”

His group looks beyond political or ethnic lines to provide relief to fellow human beings.

“We’re trying to help anyone who suffers,” said Father Movsesian, “and the reason is because we at one time suffered, too.”

Perhaps 150 people attended the forum on Saturday. The significance of the date – 7-7-7 – came from the words of Jesus, the group said: “Lord, how many times must I forgive someone who has hurt me? Not seven times, but seven times seventy-seven times.”

Among the speakers featured was Ben Kayumba, field activities coordinator for Solace Ministries, which tends to orphans and widows in the devastated African nation of Rwanda. He had lost 152 members of his family, including both of his parents, during the 100- day genocide. But he said that forgiveness has allowed him to cope with his pain.

The forum was hosted by In His Shoes, a group founded by young people, who in light of the Armenian Genocide, say that those who have suffered evil have a responsibility to take action against injustice to others. Artist Gregory Beylerian photographed each of the forum’s participants in a stance symbolic of forgiveness, which he will use to patch together a piece of art in honor of the event’s theme.

Armenian rock star Gor Mkhitarian played his signature blend of modern and Armenian folk music for the crowd at the forum.

On Friday, the group showed the film Sand and Sorrow to an audience of more than 200. The documentary, produced by Paul Freedman – who attended the event – and narrated by George Clooney, explores the atrocities currently unfolding in Darfur. An estimated 2.5 million people have been displaced there, and more than 400,000 have died so far.

And the filmmakers also examine the international community’s failure to act.

In addition to examining historical atrocities, the group has focused on trying to draw attention to contemporary tragedies, like those taking place daily in Darfur.

The Pasadena-based In His Shoes is dedicated to anyone who suffers for any reason, including all of those affected by genocide, war, or other strife. It recently joined an antiwar protest in Los Angeles, lamenting the fact that nearly 4 million Iraqis have fled their homes since the war’s start.

He said that instead of sending in “peacekeeping” troops with guns and bombs, those who seek peace should instead try to place themselves in the shoes of those who are suffering.

“We tried it in Iraq and it didn’t work,” he said. “You can’t just send in troops anywhere you have problems.”