Encountering Anew: Vazken I

by Fr. Vazken Movsesian

When His Holiness Vazken the First was elected in 1955 to head the Armenian Apostolic Church, Armenia was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union. The Cold War was in full swing and the Iron Curtain was more than a convenient metaphor. It very definitely separated East from West. The notion of a Church – a sacred and established religious institution—surviving in a system which preached atheism sounded absurd to many. But there, in the shadow of Biblical Mt. Ararat and in the place where Jesus Christ descended to mark the spot where the first Christian Nation would build the first cathedral, the Armenian Church was overtly being driven by the power of the Holy Spirit. During the 39 years that followed, Catholicos Vazken led the Armenian Church with wisdom and divine grace against the internal and external threats that were beating on an already fragile church. In 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the proclamation of Armenian Independence, the first papers of citizenship, most deserving, were given to this Venerable Patriarch. He had overcome obstacles, met challenges, delivered the Church to the doorsteps of the new millennium and in so doing, managed to inspire generations of us.

During the years as Catholicos, to many of us living in the United States – as well as in most parts of the Diaspora – His Holiness Vazken I was the embodiment of the Armenian Church. Think not in terms of the 100+ years that have removed us from the atrocities of 1915, rather imagine a time when only a few decades separated us from those memories. It was common to attend an Armenian gathering and sit side-by-side with a survivor of the Genocide – to hear her story or see his pain. It was a time when a survivor from Van would share his story with another from Kharpert or Izmir, and yet another from Tomarza. Improbable as it may sounded – the ideas that survivors of a Genocide, pulled from the homeland by mass exiles and marches, would find themselves on the other side of the globe meeting and visiting with others who shared their plight – it was happening. And the most common place where these meetings took place were under the domes of the Armenian Churches which decorated the diaspora landscape.

His Holiness expressed himself about the Diaspora while Independence was only a dream and a hope, while Glasnost and Perestroika(remember those words?) were yet to enter the Western lexicon.

… In the future, the framework for a return to the Homeland may be established. And, in fact, it is likely that such programs for repatriation will be organized. As the Catholicos all Armenians, we will be the first to offer prayers and rejoice on the occasion. … The existence of the diaspora should not be a source of fear and despair. On the contrary, destiny has thrust upon us the diaspora – a challenge which we must confront with courage and honor, structuring our life on a firm and enduring foundation of today, tomorrow… the strongest, the safest and the most reliable foundation upon which the structure of the entire Diaspora can be built today is and always will be the Armenian Apostolic Church – our Mother Church. (Paris, 1979)

| ACYO Central Council 1960, San Francisco |

I have many memories of the great Pontiff as do many others. I was honored to be given his name as a crown upon my ordination. But my first encounter with His Holiness would not be remembered had it not been for a very special photograph. I was four years old and my parents were in ACYO when His Holiness made his first visit to the United States in 1960. The ACYO Central Council had an audience with His Holiness in San Francisco and I was there. A shutter clicked and I had my first memory. My parents framed and placed that picture prominently in our home. His Holiness was larger-than-life, and the photograph would fortify that largeness every time I looked at it. His kind face was contrasted by the long black robe he donned, overshadowing the four year old little boy next to him. This was the beginning of the 1960s. A few years later, this decades was to be defined by protests, distrust for government and institutions. Individual identity was being defined along ethnic lines, Civil Rights were being demanded for all, and that picture of Vazken the First was something I could point to and claim as ours.

In the Los Angeles area, as well as throughout the world, we were coming to terms with our living in the diaspora and the ugly reality which caused the diaspora phenomenon. We heard the stories of mass atrocities from our grandparents and collectively we demonstrated for justice. In Montebello, the Armenian Genocide Martyrs Memorial Monument was being planned. My father was on the building committee for this structure and as children we were there for all the milestones: groundbreaking, fundraisers and endless speeches. Then in 1968, the Monument was to open to the public. His Holiness Vazken I was there from Armenia. His presence, his charisma, his mannerism and his words said in a united voice for All Armenians: the Armenians have arrived. There is no hiding the truth! The Genocide will never be forgotten.

In the Los Angeles area, as well as throughout the world, we were coming to terms with our living in the diaspora and the ugly reality which caused the diaspora phenomenon. We heard the stories of mass atrocities from our grandparents and collectively we demonstrated for justice. In Montebello, the Armenian Genocide Martyrs Memorial Monument was being planned. My father was on the building committee for this structure and as children we were there for all the milestones: groundbreaking, fundraisers and endless speeches. Then in 1968, the Monument was to open to the public. His Holiness Vazken I was there from Armenia. His presence, his charisma, his mannerism and his words said in a united voice for All Armenians: the Armenians have arrived. There is no hiding the truth! The Genocide will never be forgotten.  My dad gave me a small camera that day to photograph the scenes. He was busy with the organizing efforts involving thousands of Armenians and dignitaries who had come to pay respect to the past but also to celebrate the presence of the leader of the most ancient Christian tradition on Earth. To this day I remember that camera – a Mansfield using 127 film. I snapped away and with each click of the shutter I was building a library of memories that would serve as the platform for my future ministry. His Holiness had given the community a booster shot to stay vigilant in the quest for justice. But for this young boy, it was among my first major dose of the vaccination against apathy and indifference. Even going to school during those days was a pleasure because I didn’t have to search for current events: I was living through history.

My dad gave me a small camera that day to photograph the scenes. He was busy with the organizing efforts involving thousands of Armenians and dignitaries who had come to pay respect to the past but also to celebrate the presence of the leader of the most ancient Christian tradition on Earth. To this day I remember that camera – a Mansfield using 127 film. I snapped away and with each click of the shutter I was building a library of memories that would serve as the platform for my future ministry. His Holiness had given the community a booster shot to stay vigilant in the quest for justice. But for this young boy, it was among my first major dose of the vaccination against apathy and indifference. Even going to school during those days was a pleasure because I didn’t have to search for current events: I was living through history.By the early ‘70s I had felt the call to enter the priesthood. After completing my undergraduate work my studies continued at the Seminary of Holy Etchmiadzin. During that time, I took it all in. Travel to Armenia was limited. There was also a sense of isolation and loneliness being there. 1977 technology included a broken-down phone system in Armenia which made my reliance on the postal system the only hope of connecting with family and friends. A letter would take about a month to get to America and another month to get back, and of course, envelopes arrived opened, read and sometimes missing items such as the coveted powdered coffee sent to me by my mom.

|

| With my sister, January 1978 |

But His Holiness was sensitive to my plight. Even as head of the worldwide Armenian Church, he was always available for a fatherly talk. He approved my bishop’s request to ordain me into the diaconate and even arranged for my sister to visit while I was on Winter break. During the school year he taught a class in psychology. I was blessed to sit in on those classes. Considering psychology was my undergraduate degree I was in awe of how current and relevant His Holiness’ lectures were, how he engaged students in the learning process and challenged us with his assignments.

|

| Easter Week 1978 |

After returning from Etchmiadzin I continued my graduate studies at USC until the time came for my ordination. September 26, 1982 on the feast of the Holy Cross of Varak, I was ordained into the sacred priesthood by Archbishop Vatché Hovsepian and given the name Vazken. It turned out, said Archbishop Hovsepian, that it was exactly 27 years to the day that His Holiness Vazken I was ordained and out of respect to him he ordained the youngest priest with that name. In fact, the honor was to be mine; it was an honor of a lifetime to be named after a living hero of the Armenian Church and the Armenian people.

The 60’s and 70’s were times of change, of revolution and understanding ourselves as the agents of change. The music called us to activism and the atmosphere called us to reach out to one another to improve the world we had inherited and borrowing from our children. His Holiness Vazken the First was a mentor and a living example of an activist for justice. He was a revolutionary who understood the value of diplomacy and knew well how to exercise his options for the betterment of his people.

|

| Blessing in San Francisco 1987 |

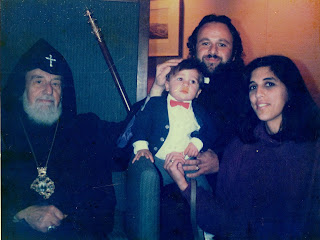

The last time I saw His Holiness was in 1987 when he made his third and final pontifical visit to the United States. By this time Susan and I had our first son Varoujan. He blessed us as a family. Coincidently we were once again in San Francisco for this blessing. Click. I keep that picture hanging in our home as a reminder and inspiration of what the Church must be and can be through its leadership.

If ever there is an overt display of the Holy Spirit guiding the Holy Church, it was during the pontificate of His Holiness Vazken the First. He led the Church during the Cold War. He was attacked by atheist ideologies from the outside. From the inside, party factions and the ugliness of divisiveness ate away at him. The church was being played as a pawn in a game but he met each challenge with love in his heart – love toward God and toward every one of his children in the Armenian nation. Without discrimination he cared about all of his children. As he ascended to the Apostolic Seat of St. Thaddeus and the Holy Throne of St. Gregory the Illuminator he kept firm to his Faith and his calling. He led with courage and valor. He articulated the primary goal of the Armenian Church “is to be the true messenger of the Gospel and to herald the Good News of Jesus Christ to the Armenian people.” He did not compromise himself nor his principles.

Twenty five years have passed since his passing. Today we invite you to Encounter Anew Vazken the First of Blessed Memory.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!